George Dodd came to Spitalfields to write this account for Charles Knight’s LONDON published in 1842. Dodds recalls the rural East End that still lingered in the collective memory and described the East End of weavers living in ramshackle timber and plaster dwellings which in his century would be “redeveloped” out of existence by the rising tide of brick terraces, erasing the history that existed before.

Spitalfields Market

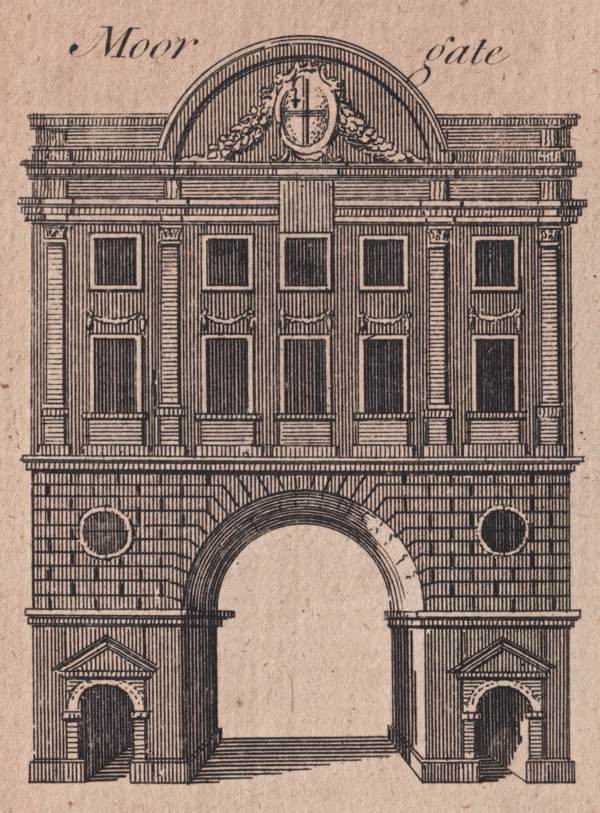

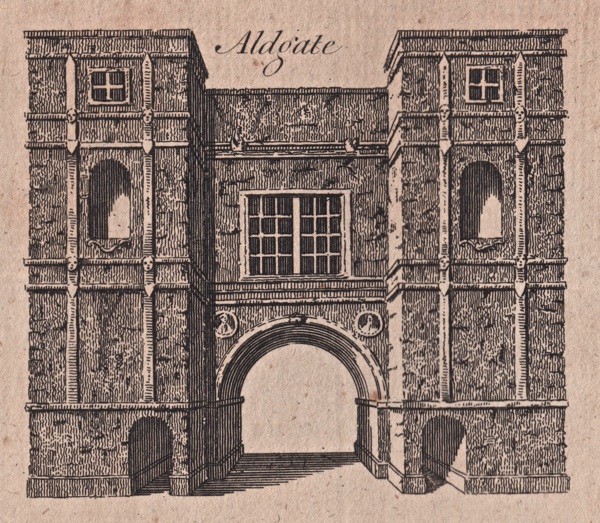

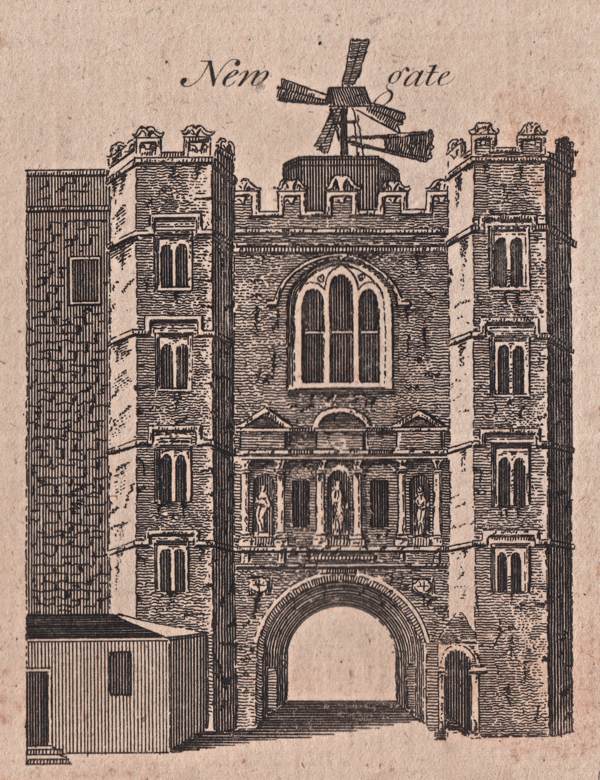

It is not easy to express a general idea respecting Spitalfields as a district. There is a parish of that name but this parish contains a small portion only of the silk weavers and it is probable that most persons apply the term Spitalfields to the whole district where the weavers reside. In this enlarged acceptation, we will lay down something like a boundary in the following manner – begin at Shoreditch Church and proceed along the Hackney Rd till it is intersected by Regent’s Canal, follow the course of the canal to Mile End Rd and then proceed westward through Whitechapel to Aldgate, through Houndsditch to Bishopsgate, and thence northward to where the tour commenced.

This boundary encloses an irregularly-shaped district in which nearly the whole of the weavers reside and these weavers are universally known as “Spitalfields” weavers. Indeed, the entire district is frequently called Spitalfields although including large portions of Bethnal Green, Shoreditch, Whitechapel and Mile End New Town. By far the larger portion of this extensive district was open fields until comparatively modern times. Bethnal Green was really a green and Spitalfields was covered with grassy sward in the last century.

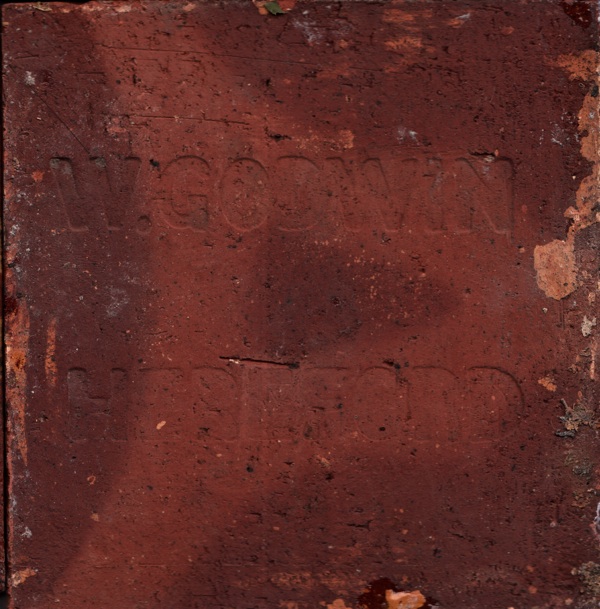

It may now not unreasonably be asked, what is “Spitalfields”? A street called Crispin St on the western side of Spitalfields Market is nearly coincident in position with the eastern wall of the Old Artillery Ground and this wall separated the Ground from the Fields which stretched out far eastward. Great indeed is the change which this portion of the district has undergone. Rows of houses, inhabited by weavers and other humble persons, and pent up far too close for the maintenance of health, now cover the green spot now known as Spitalfields.

In the evidence taken before a Committee in the House of Commons on the silk trade in 1831-2, it was stated that the population of the district in which the Spitalfields weavers resided could be no less at that time than one hundred thousand, of whom fifty thousand were entirely dependent on the silk manufacture and remaining moiety more or less dependent indirectly. The number of looms seems to vary between about fourteen to seventeen thousand and, of these, four to five thousand are unemployed in times of depression. It seems probable, as far as the means exist of determining it, that the weavers are principally English or of English origin. To the masters, however the same remark does not apply, for the names of the partners in the firms now existing, point to the French origin of manufacture in that district.

A characteristic employment or amusement of the Spitalfields weavers is the catching of birds. This is principally carried on in the months of March and October. They train “call-birds” in the most peculiar manner and there is an odd sort of emulation between them as to which of their birds will sing the longest, and the bird-catchers frequently lay considerable wagers on this, as that determines their superiority. They place them opposite each other by the width of a candle and the bird who sings the oftenest before the candle is burnt out wins the wager.

If we have, on the one hand, to record the unthrifty habits and odd propensities of the weavers, let us not forget to do them justice in other matters. In passing through Crispin St, adjoining the Spitalfields Market, we see on the western side of the way a humble building, bearing much the appearance of a weaver’s house and having the words “Mathematical Society” written up in front. Lowly and inelegant the building may be but there is a pleasure in seeing Science rear her head in a locality, even if it is humble one.

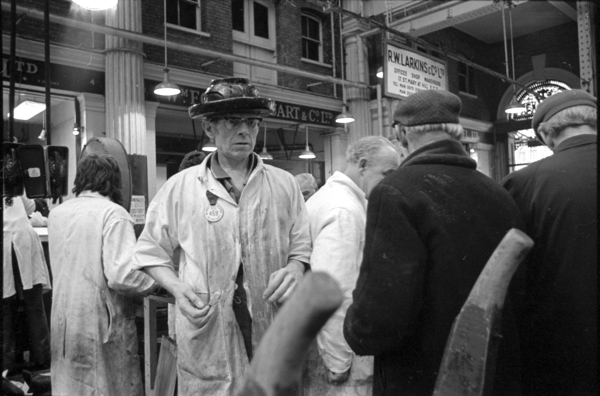

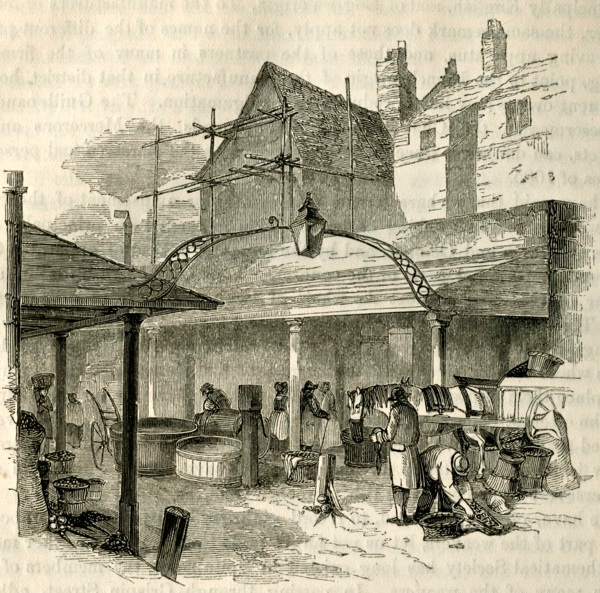

A ramble through Bethnal Green and Mile End New Town in which the weavers principally reside, presents us with many curious features illustrative of the peculiarities of the district. Proceeding through Crispin St to the Spitalfields Market, the visitor will find some of the usual arrangements of a vegetable market but potatoes, sold wholesale, form the staple commodity. He then proceeds eastwards to the Spitalfields Church, one of the “fifty new churches” built in the reign of Queen Anne and along Church St to Brick Lane. If he proceed northward up the latter, he will arrive, first, at the vast premises of Truman, Hanbury & Buxton’s brewery, and then at the Eastern Counties Railway which crosses the street at a considerable elevation. If he extends his steps eastwards, he will at once enter upon the districts inhabited by the weavers.

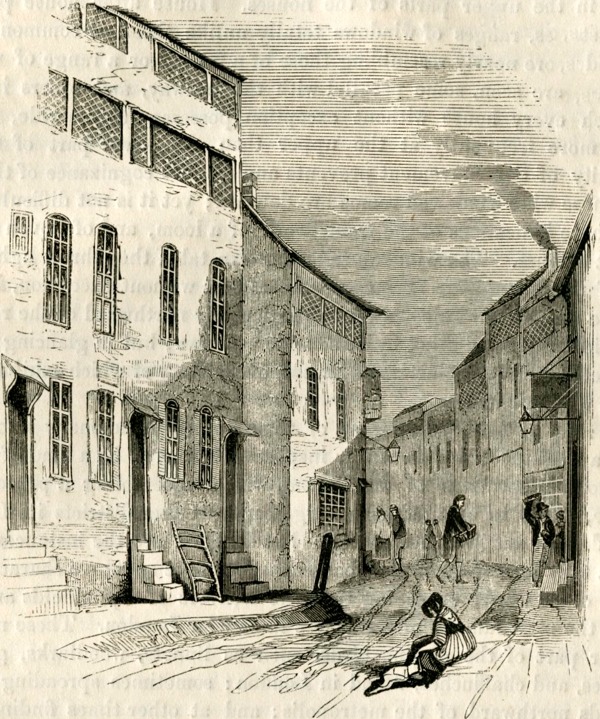

On passing through most of the streets, a visitor is conscious of a noiselessness, a dearth of bustle and activity. The clack of the looms is heard here and there, but not to a noisy degree. It is evident in a glance that many of the streets, all the houses were built expressly for weavers, and in walking through them we noticed the short and unhealthy appearance of the inhabitants. In one street, we met with a barber’s shop in which persons could have “a good wash for a farthing.” Here we espied a school at which children were taught “to read and work at tuppence a week.” There was a chandler’s shop at which shuttles, reeds and quills, and the smaller parts of weaving apparatus were exposed for sale in a window in company with split-peas, bundles of wood and red herrings. In one little shop, patchwork was sold at 10d, 12d and 16d a pound. At another place was a bill from the parish authorities, warning the inhabitants that they were liable to a penalty if their dwelling were kept dirty and unwholesome, and in another – we regretted this more than anything else – astrological predictions, interpretations of dreams and nativities, were to be purchased “from three pence upwards.”

In very many of the houses, the windows numbered more sheets of paper than panes of glass and no considerable number of houses were shut up altogether. We would willingly present a brighter picture, but ours is a copy from the life.

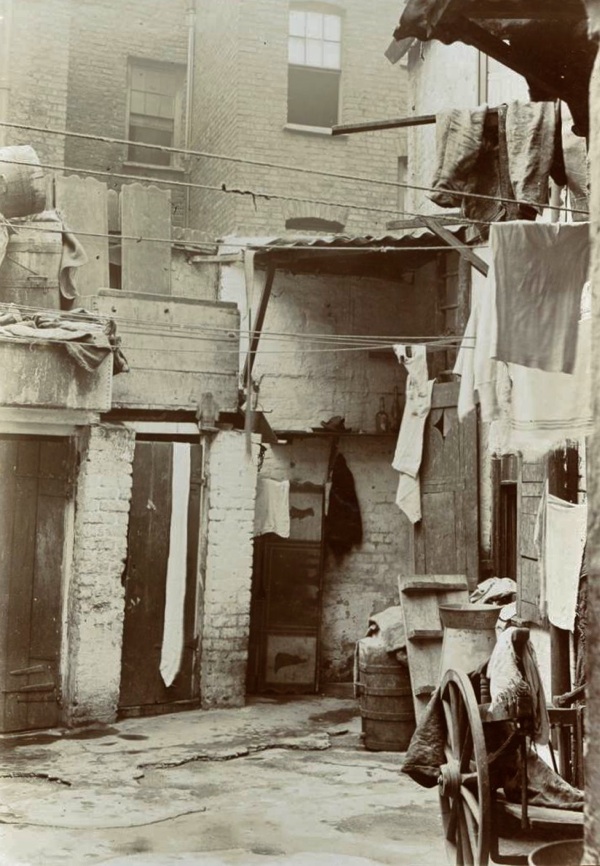

Pelham St (now Woodseer St), Spitalfields

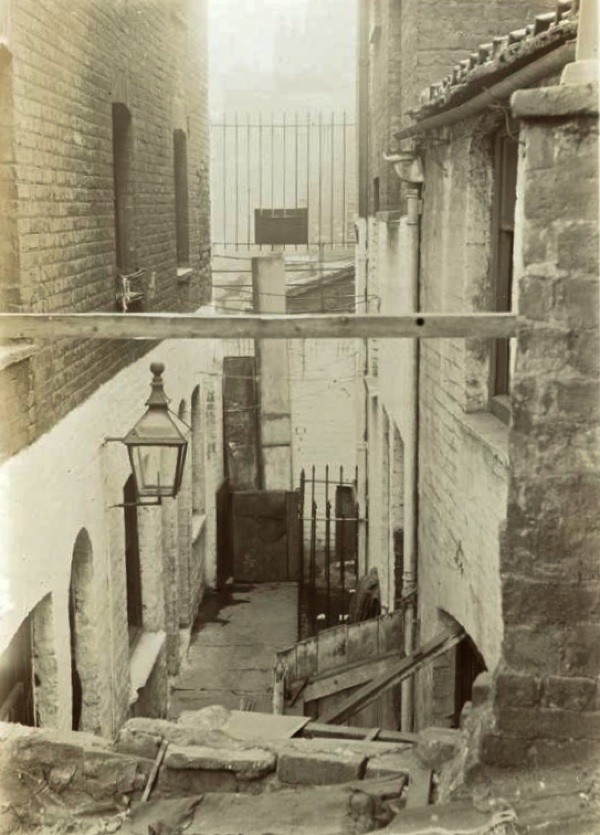

Booth St (now Princelet St), Spitalfields

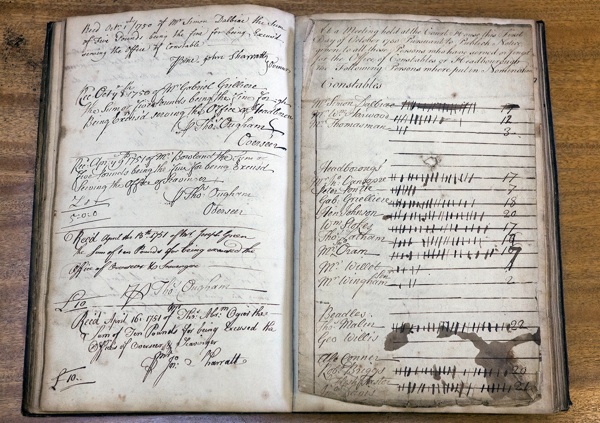

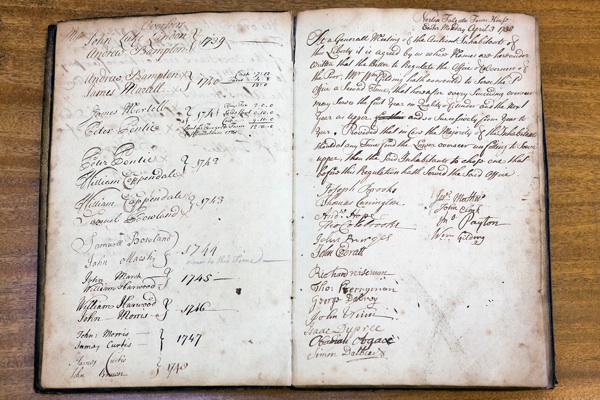

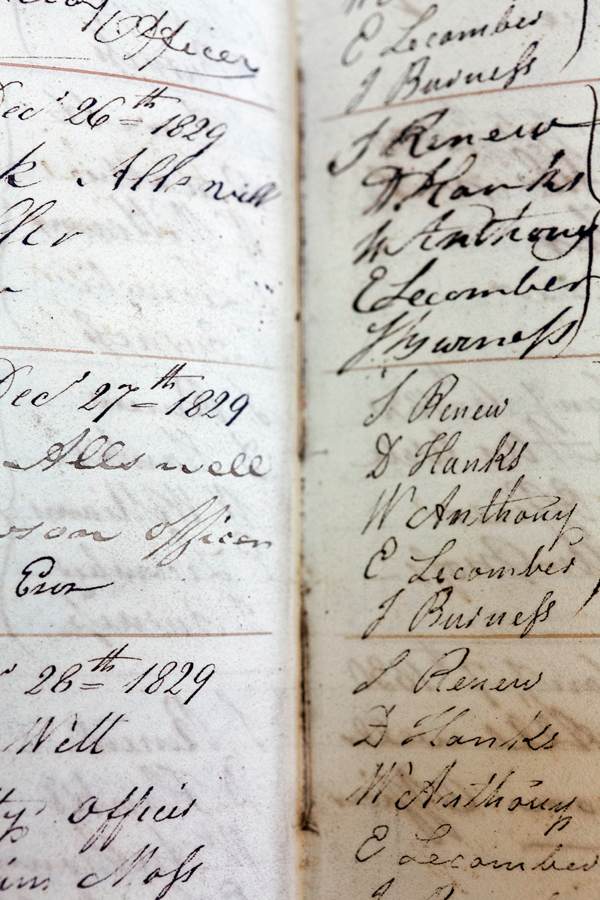

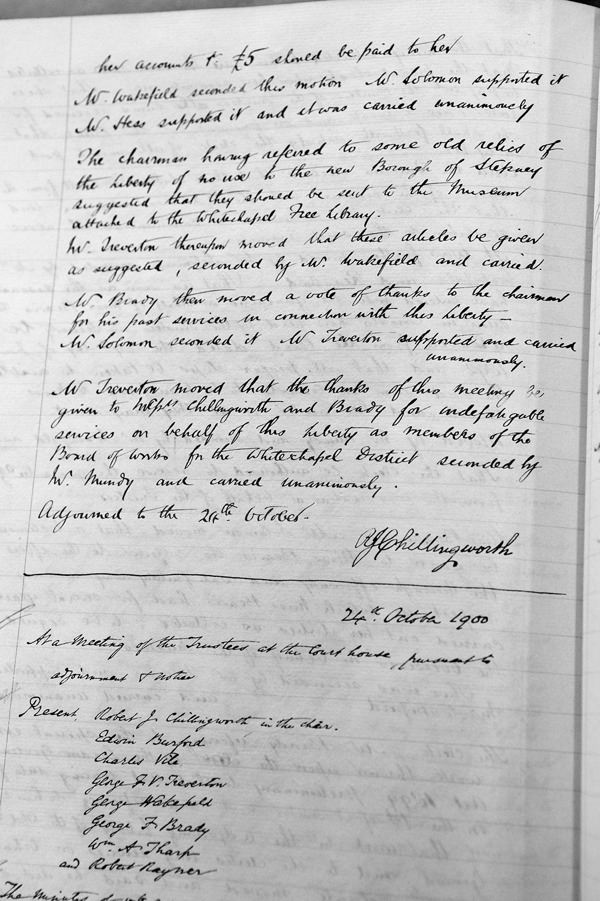

Images courtesy © Bishopsgate Insitute

![Blossom Street Exhibition Invitation[1]](http://spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Blossom-Street-Exhibition-Invitation11.jpg)

![Blossom Street Exhibition Invitation[2]](http://spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Blossom-Street-Exhibition-Invitation2.jpg)